Discovery of the next potato – Solein®

The food revolution of Solein in the 21st century will be like the potato in the 16th.

“It was a small round object sent around the planet, and it changed the course of human history.”

– Steve Hendrix, Washington Post

The coming impact of new microbial food like Solein® will both revolutionise what we eat but will also become so ordinary that we won’t bat an eyelid. That is what happened with the potato in the 16th century.

You can’t really get more commonplace than the potato. The ubiquitous starchy tuber is everywhere. In our chips, crisps, fries, mashes, salads, dumplings and it can be boiled, roasted, baked, stewed and so on. A wonderfully versatile vegetable.

It’s the world’s fifth-largest food crop after sugar cane, maize (corn), rice and wheat. Compared to the other crops though, the introduction of potatoes to world agriculture was probably the most revolutionary in history. It effectively ended famine and gave rise to modern industrial agriculture.

A discovery worth more than gold

“To ecologists, the Columbian Exchange is arguably the most important event since the death of the dinosaurs.”

–Charles C. Mann in his book 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created

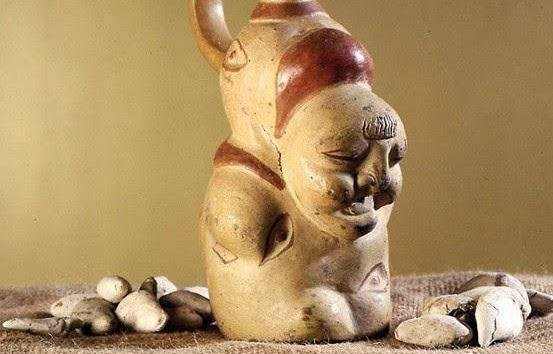

The Spanish conquistadors first encountered the potato when they arrived in Peru in 1532 looking for gold. One could argue the potato enriched the world much more than the gold Pizarro looted. Potatoes were unknown outside the Andes before the arrival of Europeans to the Americas, which is mindboggling now that they are a staple in many European national dishes. There were no tomatoes in Italian food and no chillis in Indian or Chinese food either.

The Columbian Exchange was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the Americas and the Old World in the 15th and 16th centuries. Conquerors and explorers from Western Europe took chilli peppers, papayas, peanuts, tobacco, tomatoes, maize, and hundreds of other species from the Americas and introduced them to their home countries and the trade routes of Asia.

Potatoes created a resilient Europe

What made the potato functionally so different is that, unlike grains, potatoes packed up to four times more calories per acre than Europe’s previous staples. Also unlike grains, potatoes contain sufficient nutrients to serve by themselves as the basis of a reasonably healthy diet.

For a commoner just coming out of the Middle Ages, potatoes growing underground could weather cold summers much better than leafy vegetables, did not spoil as fast and could be stored for the winter. This, in a time without refrigeration, was a matter of life and death. It is said the traditional Irish peasant meal consisted of potatoes and milk and not much else, which if eaten in sufficient quantity is a surprisingly nutritious, if monotonous, diet.

Before the potato, European countries could not feed themselves; they had an enormous problem with frequent famines. France had 40 nationwide famines between 1500 and 1800, more than one per decade. The potato changed all that. Potatoes freed up land use. Farmers could let their soil rest from constantly growing wheat and grow potatoes instead. The next year they could get a better wheat crop with fewer weeds. Because potatoes were so productive, the effective result was to double Europe’s food supply in terms of calories.

Potatoes required the influencers of their day

Even with the knowledge of this amazing new food tech, people were hesitant to try it. The philosopher Denis Diderot bashed the potato in his Encyclopedia in 1751, “It cannot be regarded as an enjoyable food, but it provides abundant, reasonably healthy food for men who want nothing but sustenance.”

In addition to its bland taste, it was rumoured potatoes were an incarnation of evil because they weren’t mentioned in the Bible and looked like the skin of lepers. Originally people would also mistakenly eat the berries of the potato, which were poisonous. Generally, the newness and foreignness of the species created a general apprehension towards the plant. One trait that was met with a great degree of suspicion was that potatoes didn’t require seeds to be grown, a first for European agriculture.

The potato didn’t take on right away, so political will was needed. In the 18th century many European Greats, including Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia, encouraged the cultivation of the potato, with Frederick even ordering the people to eat them. Marie Antoinette in France wore potato blossoms in her hair and inspired a brief bout of fashion with French nobles sporting potato flowers in their lapels.

An everyday revolution and the advent of industrial agriculture

“For the first time in the history of western Europe, a definitive solution had been found to the food problem”

– Belgian historian Christian Vandenbroeke

By the end of the 18th century, potatoes had completely changed European diets. Potatoes were as common in European diets as they had been in the Andes. Ireland was the most dependent on potatoes, 40% of the Irish ate no other solid food, but the Dutch, Belgians, Prussians and Poles were not far behind. Meat was a welcome addition to any dinner table, but it was not a necessity anymore.

Potato-based diets had the revolutionary effect of ending frequent famines. And revolutionary in a very literal sense, because political revolutions could take place amongst a peasantry that was able to finally feed itself.

“It’s hard to imagine a food having a greater impact than the potato,” — Nancy Qian, Professor at Northwestern University.

European farmers did not use the thousands of varieties of potato that the Incas had; they relied on a select few. The first intensive fertiliser was also a product of the Columbian Exchange from Peru. It was guano, the nitrogen-rich bird and bat excrement that piled up over the Andes and Pacific Islands over the centuries. Before the invention of chemical fertiliser, European countries were falling over themselves to get in on guano mining for their economies, which were all heavily dependent on agriculture.

To maximize crop yields, farmers planted ever-larger fields with a single crop; this practice would later be called industrial monoculture. That is how crops are mostly grown today.

Monoculture makes the plant extremely susceptible to pests and diseases. The Irish potato blight is the most infamous example of this, killing 25% of Ireland’s population in the middle of the 19th century. Potato blights had the inadvertent effect of making potato the first plant that had chemical pesticides developed for it. Paris Green, a poisonous green combination of copper and arsenic, was first sprayed on potato leaves in 1814. It has now been discovered that the fungus that caused the potato famine originated in the guano shipments from South America to Europe.

Our food system needs to be shaken to its roots

Famine still exists but at a significantly lower level thanks to refrigeration, logistics and fertilisers. Humanity faces more existential crises though. With the world population estimated to hit 9.9 billion by 2050, the present level of food (and especially protein) production is hard-pressed to keep up.

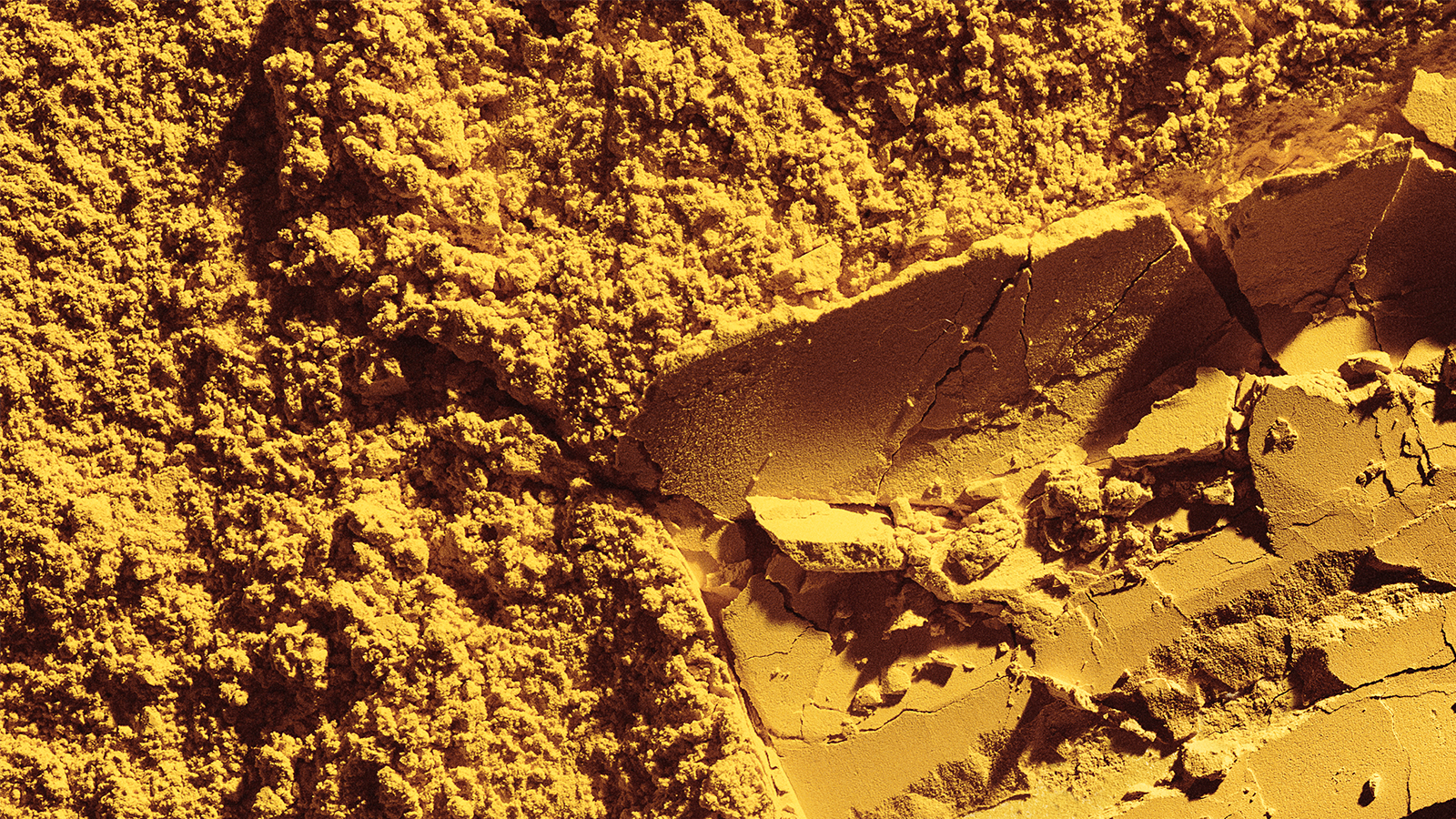

With the agriculture of today, we will not have enough land, water and resources to sustain so many people without completely wrecking our ecosystem. Agriculture is already at an unsustainable level and climate change is destroying arable land with desertification and drought. Pesticides, pollution and the plight of factory-farmed livestock are also perennial problems. What can forward-thinking leaders get behind to solve these issues?

Solein – a discovery for our time

“I’d compare Solein to the discovery of the potato: we are introducing an entirely new crop for humanity to harvest. It’s a watershed moment for how we think about food.”

–Pasi Vainikka, Solar Foods

Solein is a food ingredient that rivals the potato in its implications for humanity. It is a nutritious protein-rich powder, made up of single-cell organisms that are fed carbon dioxide and hydrogen instead of fertiliser and water. It’s an answer to many of the food production problems faced by humanity.

Farming Solein at scale takes the pressure out of traditional farming. A world that shifts its protein production to use more Solein instead of factory-farmed animals and industrially grown plants doesn’t need to cut down rainforests for fields or pastures, and can increase biodiversity through rewilded fields, crop rotation and organic farming. There will still be enough food to feed the world. Solein is not susceptible to crop failures from natural or man-made disasters or monocultural blights.

Solein will not replace familiar foods either, just like New World potatoes didn’t replace Old World turnips. It just added to the diversity of the foods we eat.

The mental leap into the microscopic

Like with the potato, the biggest leap people will have to make is mental. The entire world became all the richer in food diversity after the Columbian exchange. Once people are comfortable eating something new, culinary innovations begin to appear. French fries were invented in Belgium more than a century after potatoes were introduced. This time we don’t have to wait a century to find out what new treats await.

Singapore was recently the first country in the world to approve Solein for general consumption. In their decision, Singapore’s leaders demonstrated that they are for food autonomy, resilience, and new culinary innovations. Solein can be a reliable staple of a food system but it is also incredibly versatile, since it can be used as an ingredient in any food, and it can taste like anything. Different Solein applications are already being tested.

Solein is a food that does not have seeds or bones, so it might feel outlandish. But like the potato, it is something we can eat that has been with us for ages, just hidden from sight. We had to travel to a microscopic New World to find it. We’ve now come back with our bounty that is more precious than gold, but it can become just as commonplace as the potato has.